Donald Trump’s rise to the presidency thrust far-right groups into the spotlight. But on the other end of the political spectrum, socialist organizations across the country are quietly experiencing a surge in popularity of their own, driven in part by Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ outsider campaign last year and a determination to thwart President Trump’s policy agenda.

The Party of Socialism and Liberation’s meetings have tripled in size at the group’s New York headquarters in the months since Trump won the election. And the Democratic Socialists of America’s membership has more than doubled to 19,000 activists since Sanders, a self-described Democratic socialist, launched his presidential campaign in 2015.

The last time the Democratic Socialists of America saw such growth was in the early 1980s, said Joseph Schwartz, a member of the group’s national committee. “People feel like they have to fight back,” said, Schwartz, who teaches political science at Temple University.

But with interest in socialism on the rise, insiders are struggling to figure out how socialist groups will fit into the Democratic Party, and what role they’ll play in the left’s opposition to Trump’s presidency.

Socialism has long been at the fringe of center-left politics in the United States. But activists like California Tech graduate student Charles Xu said Sanders’ presidential campaign was a new wake up call.

“Bernie’s self-identification as a socialist normalized it,” Xu said in a phone interview.

Xu said he first encountered socialist politics on trips to Europe in the past few years.

After the 2016 election, Xu and a friend founded the Cal Tech chapter of the Young Democratic Socialists, the student arm of the national Democratic Socialist of America organization.

“We’re on the cusp of a moment that can be really exciting,” he said.

What the moment represents, though, is not yet entirely clear.What the moment represents, though, is not yet entirely clear — especially given the left’s recent electoral setbacks at the federal, state and local level. In 2016, Democrats were crushed in state races. Now, only five states have Democratic-controlled state legislatures and Democratic governors; 25 states have complete Republican control. Democrats lost a presidential election that many thought was in the bag, and Republicans maintained control of Congress.

The losses sparked a period of soul-searching in Democratic Party establishment circles. But it also energized grassroots activists around issues like immigration, women’s and civil rights and criminal justice.

Registered socialists and others friendly to the cause “are not just paying dues [to organizations] like the ACLU,” Schwartz said. “They want to make progressive gains.”

It’s no coincidence that the movement’s policy goals seem similar to Sanders’ talking points during his White House run. The Democratic Socialists of America endorsed Sanders, and many of its members worked on his campaign. More than 6,500 people joined the organization after Sanders jumped into the race, Schwartz said.

“There is [a] desire to deepen what Sanders started,” he said, adding: “There is a push to move Democrats away from neoliberal policies and corporate donors.”

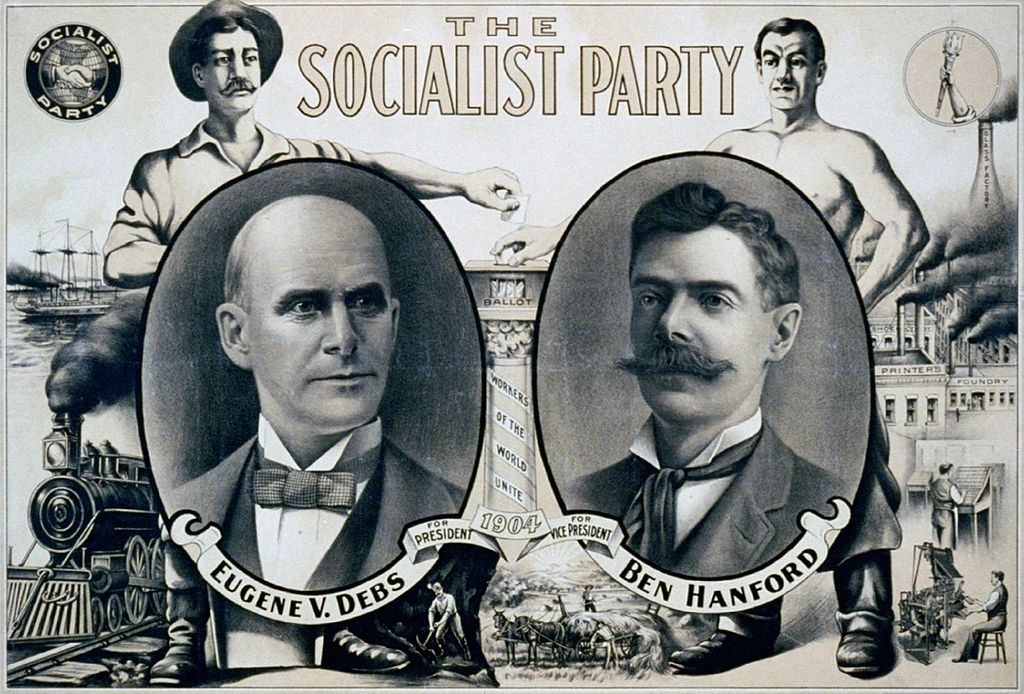

A 1904 campaign poster for Eugene Debs, a socialist leader who ran for president five times in the early 20th century. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

This isn’t the first time Americans have looked to socialism to solve society’s woes. In the early 20th century, many Americans began to view “socialism as a solution to broader problems,” like wealth inequality, urban poverty and child labor, said James Barrett, a history professor at the University of Illinois.

The Socialist Party of America, which was formed in 1901, “had deep influence in some unions, especially [ones] with immigration members like the garment manufacturing unions,” Barrett said. “On the state level there was a lot of electoral success in a lot of smaller industrial towns, too.”

Milwaukee liberals, for example, embraced “sewer socialism” as a means to reform the city’s political corruption and improve its unsanitary conditions. In 1910, voters from Milwaukee elected Victor Berger to the U.S. House of Representatives, making him the first socialist to serve in Congress.

Eugene Debs, who formed the Socialist Party with Berger and other activists, represented the movement on a national level, becoming a household name thanks to his five presidential bids between 1900 and 1920. For his 1920 campaign, Debs received nearly a million votes in the general election, despite being in jail for violating the Espionage Act.

At the time, the Socialist Party was a diverse voting bloc that included immigrants, Southern farmers, Christian socialists, urban intellectuals, and writers and activists like Upton Sinclair and Helen Keller, Barrett said. But the Socialist Party’s popularity was short-lived. Membership declined because of the party’s opposition to World War One, and support for the Russian revolution, Barrett said.

“The Russian revolution affected how Americans viewed socialism,” by creating a negative association between the U.S. Socialist Party and Russian-style socialism that never entirely went away, Barrett said.

A century later, today’s socialist movement has changed with the times in some ways. Activists add rose emojis to their Twitter profiles, instead of wearing the black armbands that were popular when Debs was a perennial White House contender. But 21st century socialist groups in the U.S. have continued struggling to make inroads into the mainstream Democratic Party. Sanders did better than many people expected in 2016, but still wound up losing the party’s primaries to Hillary Clinton after failing to win over its establishment wing.

Sen. Bernie Sanders, a self-described Democratic socialist, speaks at a campaign rally in Stockton, California on May 10, 2016. His presidential campaign helped spark new interest in socialism in the U.S. Photo by Max Whittaker/Reuters

The intraparty fight continued after the election, when Rep. Keith Ellison (D-Minn), a Sanders supporter, ran for chairman of the Democratic National Committee against Tom Perez, a former Labor Department secretary and Clinton backer. Perez won in a close vote, but named Ellison as DNC vice-chairman, giving the progressive wing of the party a top leadership slot.

And polls show Sanders’ popularity hasn’t diminished months after the election ended. A recent Fox News poll found that Sanders was the country’s most popular politician. Sixty-one percent of Americans viewed the Vermont senator favorably, the poll found, far outpacing other Democrats and Republicans like Trump and House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI).

There are other signs, too, that interest in socialism and Sanders’ liberal policy agenda could have some staying power. Jacobin Magazine, the country’s largest socialist publication, had about 17,000 subscribers in the run-up to last year’s Nov. 8 election, according to Bhaskar Sunkara, the magazine’s editor. It now has 30,000 subscribers, a nearly 100 percent increase in just four months.

Sunkara said the publication’s goal was to “legitimize socialist ideas” and bring them into the political mainstream. He compared it to libertarian think tanks that have helped drive conservative policy on the right in recent decades.

“With our growth, we’re planning to expand,” he said. “Basically do things in a more polished, professional way.”

Schwartz said groups like the Democratic Socialists of America hope to “create a climate where more left-wing candidates are viable” at the state and local level.

But the movement still faces plenty of opposition from the right.

“I understand why [people] fall susceptible to socialism,” said Charlie Kirk, the executive director and founder of Turning Point USA, a conservative organization that promotes limited government and free market principles on college and high school campuses.

“It sounds really good when a professor or teacher or peer talks about Denmark or Norway or Sweden,” said Kirk, whose group runs “socialism sucks” campaigns on campuses across the country. But “the free enterprise system is the most prosperous system we’ve discovered,” he said.

Schwartz, of the Democratic Socialists of America, argued that socialism was poised to become an important part of the American left. “We’re part of a broader left,” Schwartz said. “We want to be a socialist presence in a national movement for democracy.”

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2egpLmqwMicqmirn5i2orjIrKRmrZ6ewaawjKyrmqyVqHquu8yepa0%3D